David Seymour (Chim).

Photograph by Elliott Erwitt

�1996 Elliott Erwitt

David Seymour (Chim).

Photograph by Philippe Halsman

�1996 from the Estate of Philippe Halsman

(Nazario) Eliezer Tritto and his daughter Myriam, Alma, Israel, 1951. Myriam was the first child to be born in the Italian immigrant settlement in Alma.

�1996 from the Estate of David Seymour

Nahal Kibbutz in the Huleh Valley. Israel, 1952

�1996 from the Estate of David Seymour

Patrolling the border between the Negev Desert in Israel on the border of Jordan. Israel, 1952

�1996 from the Estate of David Seymour

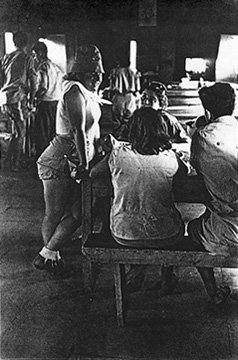

Port Said, Egypt, 1956

�1996 from the Estate of David Seymour

A woman mourns at the funeral of an Israeli watchman slain during a border incident at Beth Hafafa, Jerusalem, 1953.

�1996 from the Estate of David Seymour

|

The plight of the Jews was never far from Chim's consciousness, even,

as Cartier-Bresson described it, "with a certain sense of despair at his

own situation." However sophisticated and caring he was, however

much he enjoyed life, he was conditioned by the circumstances of his

background and by the fate of his parents in a world where anti-

Semitism was rife. The safe haven of Palestine, later Israel, for those

who had survived the Holocaust, was therefore never far from his

thoughts. In November 1947, the young United Nations passed a

resolution to partition Palestine into two new states, the State of

Israel and the State of Palestine. The latter was never formed

because the leaders of Egypt, Transjordan, Syria, Iraq, and Lebanon

rejected the partition, and immediately upon the formation of the

State of Israel, in May 1948, these five Arab nations attacked it in

war.

But it was not until October 1951, when Israel had been an

independent state for almost three years, that Chim arrived there,

having obtained from his sister all the addresses of their family in

Israel. "It will be strange to meet them after so many years!" he wrote,

and once there, "You can imagine how everything here is emotionally

charged and moving."

In those pioneering days, Israel was vibrant with the intimacy

of youth. During one of his trips, in December 1953, the newspapers

reported a not-infrequent incident: an Israeli soldier guarding some

Arab women picking olives near the border had been killed. In

heartrending photographs, Chim told the story of the funeral, and the

anguish at the sudden death of such a young man.

Chim returned to Israel almost every year until his untimely

death in 1956. As his coverage grew, it developed into a survey of the

important aspects of the young country's development: he did stories

on the all-important themes of defense of Israel's borders,

deployment of the water resources essential for irrigation, life in a

kibbutz, the development of the copper mines in the south that date back to

King Solomon's times, the oil pipeline, and other aspects of the

country's industrialization. And as time progressed, he photographed

Israel's important tourist sites. Had he lived, he would have continued

his coverage in Israel. As it is, there is enough material in Chim's

work for a book on the country's beginnings, idealistic and

enthusiastic as they were. In a way, the spirit of Chim's coverage in

Israel is reminiscent of his work during the Spanish civil war. In

those early years in Israel, there was the camaraderie,

purposefulness, and intimacy in the face of danger that he had

encountered in Spain. But there was more: he photographed the

stages of life, birth, marriage, and death. Looking at these

photographs, one cannot help feeling that Chim's soul rested in Israel,

the land of his forefathers.

Nineteen fifty-six was a busy and successful year. Chim went to

England to photograph an atomic energy installation there. He

covered the Italian elections. He once again photographed Ingrid

Bergman, his favorite subject, and other beautiful women. He

cemented new relationships with magazines: Newsweek and House

and Garden. For the latter he wrote his first text piece, scholarly and

amusing, on "The Legends of Rome." He wrestled down an

administrative monster to create an appropriate growth for Magnum,

and called the annual meeting for November 10 at which changes

would be explained and implemented.

He was in the Greek countryside enjoying a well earned vacation

when the Suez Canal crisis began, and at the same time, the

Hungarian revolution. Chim postponed the Magnum meeting for

coverage of these important events. Erich Lessing left Vienna for

Budapest. Burt Glinn was in Tel Aviv.

Chim knew it would be foolish for him to cover the Hungarian

revolution. Chim was almost forty-six years old, and he had not been

to war for twenty years. Chim thought it would be wonderful to

travel from Egypt to Israel, as the children of Israel did with Moses.

The Israeli forces advanced swiftly through the Negev onto

Egyptian soil. In Athens the press corps was excited by the news, and

frustrated trying to get to Egypt. Chim managed to obtain

transportation to Cyprus. While awaiting accreditation, he

photographed French paratroopers getting ready to fly off. There was

a day of waiting, which Chim spent reading dispatches, and also

photographing part of one of the religious festivals he loved so much.

There is a contact sheet of little girls in a procession, dressed up as

nuns and angels. The next day, Chim flew with Ben Bradlee of

Newsweek and Frank White of Time-Life to Port Said in Egypt. They

were joined by Paris Match photographer Jean Roy, known for his

war-time exploits. For the next day and a half they all drove through

the streets of Port Said. Frank White wrote:

Dave [Seymour] must have known what he was letting himself in

for. Ben Bradlee and I made no secret of the fact that we were

scared to death. But Dave, the quiet rational man, the

intellectual...said nothing. He just kept on making pictures. When

making pictures he seemed to be an entirely different man. He kept

saying, "this is a great story." I got the impression that he felt this

made him somehow impervious to risk.

On November 10, four days after the armistice, with Jean Roy

driving their jeep, Chim set out to photograph an exchange of

wounded soldiers at El Quantara. The photographers drove fast past

the Anglo-French lines and down the causeway toward the Egyptian

lines. Machine-gun bullets struck Jean Roy and Chim. The jeep turned

over. Both were dead.

Chim's body was flown back to New York. Over three hundred

people attended the memorial service for him. From Paris, Henri

Cartier-Bresson and Ernst Haas sent handwritten messages. Thinking

of Bob Capa and Werner Bischof, Ernst wrote: "Chim! As I don't

believe that death is an end, I can only say that I envy you the

company you will be in." And Henri: "Chim was a friend of mine since

24 years. I would like to just ask for a moment of silence to

meditate, as silence reaches beyond distance."

Inherent in their appreciation of the man is respect for the

quality of his photographs, for in a group bonded by the quality of

work, one is not possible without the other.

Chim styled himself a craftsman, and he had an unusual mastery

over his tools. He was devoted to the quest and sharing of

knowledge, with expert composition as the corollary in conveying this

knowledge. He was endowed with a tremendous tenderness and

great emotion. The photographs of his "Children" stand out as

haunting images, but as he progressed in age, his compositions

became more complex and more visual, a trifle less emotional. His late

work is full of his finest images. In his last years, he allowed himself

on occasion to indulge in purely visual problems, as in his outstanding

photographs involving sculpture.

There was in Chim a schism between the solid citizen who

enjoyed and recorded a variety of the concerns and pleasures of

civilized society and the artist. Witness to this dichotomy are the

splendid, original compositions and the phenomenon of the sudden,

always perfectly composed single exposures of a subject that are not

the work of a journalist, even if their content is journalistic.

In Chim there was that irrational element that is an important

part of creativity, which makes the artist in the performance of his

work feel free, and in this freedom, feel invulnerable. It is that

element on which journalist Frank White commented about Chim

photographing at Suez, just before his death, as he said, "When

making pictures he seemed to be an entirely different man ... I got

the impression that he felt this made him somehow impervious to the

risk..."

But for the lure of the story, Chim would have lived, as indeed he

had begun to live, to reconcile the brilliant aspects of his photography

with his equally brilliant ability to conduct a business whose capital

was the unruly, querulous spirit of ever-pioneering humanistic

photography.

As for the history of photography, this book is but an

introduction to Chim's work. Much more sifting, much more studying

will have to be done before we can codify David Seymour's repeated

patterns of composition and story structure, and his color work, about

which we have said nothing here. Only then will his influence on

photography be widely felt.

For now we may safely say that the scholar and humanist David

Seymour was a Renaissance man of impeccable ethics, blessed with

kindness, tolerance, modesty, and exquisite sensitivity in his

appreciation of others, of the world, and of the requirements of his

craft. Though he photographed for only fifteen years, his is an oeuvre

of distinction in the annals of modern photography.

- Inge Bondi

� 1996, Inge Bondi

from CHIM: The Photographs of David Seymour, Bulfinch Press/Little, Brown and Company

|